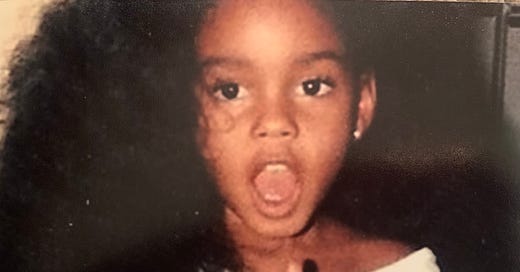

Being attractive was never something I had to convince myself of. My beauty was and is something that has always been affirmed. And honestly, if anybody ever said anything to the contrary, we both knew it was a bold-faced lie. Kinda like the ex-friend I mentioned in Is Your Friend Actually a Hater. I grew up with elder Black women, the true authority on all things, who would say things like: “You just as pretty as you wanna be.” And who am I to believe otherwise?

In fact, I can’t even say I know polarizing colorism in the way some Black folks do. I am a shade of brown, like a Crayola crayon. Rich in tone but not particularly deep and not light-skinned either. Just brown. Whether I am considered dark or light skinned depends on the audience. At home, I was the light one—my mother, stepfather, and brother had deep, radiant brown skin. And my mother? A beauty in the truest sense. High cheekbones, a bright, magnetic smile, skin flawless and rich like Naomi Campbell. I grew up watching her move through the world as an effortless and lowkey beauty. My mom may have been considered a tomboy, yet her attractiveness was undeniable. So my own association with beauty felt like a natural and obvious birthright.

If I have to return to this Earth in human form again, I only want to be in a Black body. I love being Black. And having a dark skinned mom, my first standard of beauty, I grew up admiring the way dark skin glows from within. “All features are African features” my late grandmother would say. Thus I love the way our features hold stories of where we’ve been and where we’re headed. With that, I never doubted my value or place in it.

But then we moved to the Pacific Northwest.

Suddenly, my reflection was harder to find and my knowingness became more nuanced. The sun didn’t shine the same, and neither did I. The summers that once deepened my brown to bronze were replaced by endless months of gray. My skin felt dulled. And the people around me, pale and pink-cheeked, looked at me differently whether I was sun-kissed or my winter hue. They didn’t see the diversity at which I’d come from. To my fair peers, I was Black as night.

At school, I was often the only Black girl. And in the occasional setting where there might be another brown girl, I was the only one with TWO Black parents. And while I felt like an average girl simply existing, my very existence was something that needed to be named, qualified, or explained. I was no longer just pretty. I was pretty for a Black girl.

I still remember the first time I heard it.

Summer school. A white boy I had spent 20 minutes debating music with: “Which genre of music is the most difficult to play?”—me arguing in favor of jazz, him for rock—looked at me, appraising. "You know, you're really pretty for a Black girl."

I paused. "What is that supposed to mean?"

He hesitated, confused by my reaction. "I just don’t usually find Black girls attractive, but you’re different."

I took a breath. “You know that’s not a compliment, right? Because I am Black. And I’m not the only beautiful one. Far from it.”

"Relax. I’m just saying Black girls aren’t really my preference."

The audacity. The nerve to think he was offering me something valuable.

It wasn’t the first time, and it wouldn’t be the last.

The school year before, I had a crush on a light-skinned boy at school—cool, charismatic, kinda looked like Ginuwine (it was the early 2000’s after all). It got back to him that I liked him, and one day he pulled me aside. "Hey, I heard you like me. I just want you to know that I’m flattered, but I don’t really mess with Black girls like that."

I don’t even remember what I said in response. Because even now, how does one respond to something like that? I remember feeling small and the remark stuck with me long enough to talk to my therapist about in adulthood.

At the time, it simply wasn’t en vogue to love girls like us. Not even for our own. And I took that personally. *Michael Jordan voice*

At the time, I tried to brush it off. But coming of age in an environment where your type of beauty is invisible—or worse, acknowledged only as an exception—does something to you. It makes you question the little voice inside that once whispered with certainty, You are beautiful. It turns that whisper into a murmured inquiry, then into something so faint, you can barely hear it.

In white spaces, I was too Black or “not like other Black girls” on account of my neutral accent and love for diverse music. Among some Black girls, I was too confident or perhaps obscure. But to me, I was just being myself.

By then, I had already learned that beauty is political. And to be Black and self-assured was to be audacious. It wasn’t just in classrooms or social settings that beauty became political. It followed me everywhere, even into the spaces where I was supposed to stand out.

In my commercial modeling days production would attempt to dull my features with flat makeup, or no makeup at all, claiming I didn’t need it or that they didn’t want me to outshine the others. Don’t even get me started on the ways they’d have you remove your sew-in or take down your braids for a job only to be perplexed when they realized they liked your original look all along.

And yet, even through the years of being othered, I have always seen the world through the lens of beauty.

I’ve always been moved by the presence of beauty in everything, everywhere. It can be the way a bird soars through the sky, the way branches sway when kissed by the wind, or a child’s laughter. I would argue that my ability to see beauty in the world is real reason why people see it in me. Not my color or physical attributes.

Beauty, to me, is a reflection. I have been called beautiful in every part of the world, in languages I don’t speak, by people who don’t know me. And I believe it to be 20% genetics and the remaining 80% I attribute to the way I move, the way I see, the way I take in the world with wonder.

But I also recognize beauty is a weapon.

People fear beauty will deceive them, undo them, make them question their own worth. That’s why villains in films are often beautiful women, why some people bristle when you walk into a room, why beauty can make others uncomfortable. What is she going to take from me? What power does she hold? And if you are beautiful and Black, expect that energy to magnify tenfold.

I see it happen. I can tell in a team setting when someone is going to stop liking me, when my presence will be seen as a quiet threat. It’s the reason why someone will tell me they “thought I’d be a bitch” after sharing a few moments with me. It’s the reason people project their fears or place additional barriers in front of people they consider highly attractive. There’s a weird assumption that beautiful people are without everyday challenges, but that’s a whole other topic.

Basically, the labor of beauty is appeasing the discomfort of those who question their own desirability.

But for me, I refuse to shrink for people who don’t know how to see themselves. That’s not my problem. And I don’t recommend anybody shrink for a world that benefits from making them feel small.

I was never pretty for a Black girl.

It was always just pretty, plus a whole lot more. Full stop.

I really like how you are speaking bold truth. As the mother of beautiful brown skinned daughter and son I see God’s radiance. To be told most of my adult life by men of all ethnicities “You’re beautiful for a black woman” later helped me to adjust my crown of beauty. What they are really saying is I’m limited on my communication, you intimidate me and I stumble over being genuine. My father would address me as his beautiful smart daughter and seal it with I love you and keep smiling. When you know that you are loved your beauty radiates and shines like a brand new bronze medal. I will gladly take my brown bronzed skin over silver or gold any day. Baby girl, it warmed my heart to know you saw the beauty in your mother beyond her outward beauty. You saw her inner self that she showed you how to show up beautiful in any situation. I love you.

I can relate to this so much. I heard the same phrase growing up also being the only black girl in my class in my private Christian school. Then when I finally begged my mom to let me go to public school I wasn't black enough for the other black girls and was bullied because my hair was too long or I talked "white". Then boys would tell me how they didn't really like black girls but would make an exception for me because I was pretty for a dark skin girl. Whew I'm so glad that I have grown to love the skin I'm in and I wouldn't want to be anything other than a black woman!